Exploring the vast reaches of the cosmos reveals strange phenomena that challenge our everyday experience. Among the most captivating is the warping of time itself. When spacecraft travel at high speeds or pass near massive celestial bodies, clocks tick at different rates—an effect known as time dilation. This phenomenon emerges naturally from Einstein’s theories and has profound implications for navigation, communication, and future interstellar travel.

Understanding Time Dilation: Special Relativity

Einstein’s 1905 paper on special relativity introduced revolutionary ideas about space and time. Two postulates underpin the theory: the laws of physics are identical in all inertial frames, and the speed of light in a vacuum is constant for all observers. These lead directly to the conclusion that moving clocks run slower than stationary ones when observed from an external frame.

Imagine two observers, Alice and Bob. Alice remains on Earth, while Bob journeys in a spacecraft at a significant fraction of the speed of light. According to special relativity, Bob’s onboard clock ticks slower by a factor of

- γ = 1 / √(1 – v² / c²), where v is Bob’s velocity and c is the speed of light.

As v approaches c, γ increases dramatically, making the dilation effect more pronounced. This leads to the famous twin paradox: the travelling twin (Bob) ages less than the stay-at-home twin (Alice). While the resolution involves acceleration and changes in reference frames, the core idea remains: motion through spacetime affects elapsed time.

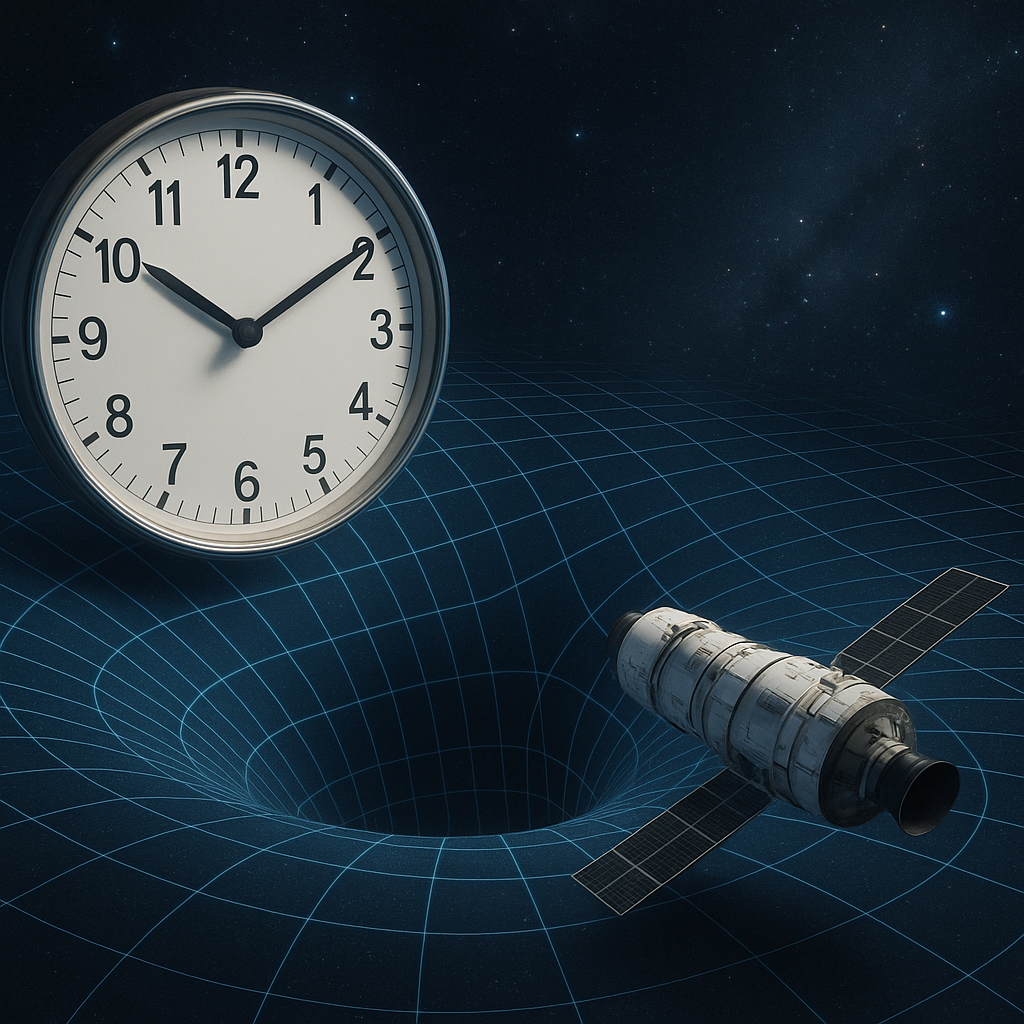

Time Dilation and Gravity: General Relativity

Special relativity neglects gravity. Einstein’s general relativity, formulated in 1915, extends the concept by describing gravity as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. A key outcome is gravitational time dilation: clocks closer to a massive object tick slower compared to those further away.

In mathematical terms, the gravitational time dilation near a non-rotating spherical mass M is given by:

- Δt₀ = Δt_f √(1 – 2GM / (rc²)), where G is the gravitational constant, r is the radial coordinate, and Δt_f is the far-field interval.

Near Earth’s surface or in orbit, this effect is small but measurable. Deep in a strong gravitational potential, such as near a neutron star or black hole, time can stretch dramatically. A few hours near a black hole’s event horizon might correspond to years for a distant observer, illustrating the extreme warping of both light paths and temporal intervals.

Experimental Evidence and Observations

Precise experiments have confirmed both special and general relativistic time dilation. Key examples include:

- Muons in Cosmic Rays: Muons created high in Earth’s atmosphere travel toward the surface. Their half-life is only 2.2 microseconds at rest, yet many reach sea level because their internal clocks run slower from our frame.

- Atomic Clocks on Jets and Satellites: In the Hafele–Keating experiment, atomic clocks flown around the world showed measurable shifts compared to stationary counterparts. Similarly, GPS satellites must account for both velocity-based and gravitational time dilation to maintain accuracy.

- Pulsar Timing: Highly regular pulses from neutron stars allow astronomers to track minute variations in arrival times, revealing relativistic effects in binary systems and confirming predictions of general relativity.

These observations not only validate theoretical frameworks but also drive technological advances. Engineers must correct for relativistic timing discrepancies in global navigation systems, ensuring that positions remain pinpoint accurate to within meters.

Implications for Deep Space Travel

As humanity sets its sights on Mars, asteroids, and beyond, time dilation will play a pivotal role in mission planning. High-speed cruise phases could reduce subjective travel time for astronauts, potentially easing the psychological burden of long journeys. However, synchronizing communications with Earth becomes more complex:

- Message delays grow not only from distance but also from relativistic offsets in clock rates.

- Maintaining lock-step navigation requires continuous recalibration of onboard and ground-based time standards.

Future proposals for near-light-speed probes or generation ships must grapple with the twin effects of motion and gravity on crew health, equipment lifetimes, and mission logistics. Furthermore, any contact with distant colonies would involve bridging temporal gaps: what seems like years on Earth might be mere months for the explorers.

Frontiers and Open Questions

Interstellar Travel and Time Windows

Interstellar mission concepts—such as Bussard ramjets or laser-pushed sails—aim to approach appreciable fractions of c. At such speeds, time dilation could reduce proper travel durations significantly. But accelerating to, and decelerating from, such velocities demands enormous energy budgets and advanced propulsion systems.

Quantum Clocks and Ultra-Precise Tests

Advances in quantum metrology offer clocks with uncertainties below 10⁻¹⁸. Placing these next to varying gravitational sources, or aboard fast-moving spacecraft, can probe minute deviations from relativity. Any anomalies might hint at new physics or the elusive quantum gravity regime.

Impacts on Causality and Information

While relativity forbids superluminal travel, relativistic effects challenge our intuitive notions of simultaneity. Understanding how information propagates through curved spacetime is vital for secure deep-space networks and for theoretical explorations of wormholes or spacetime shortcuts.