The nature of time shifts dramatically once humanity ventures beyond our planet. Far from a steady, universal metronome, time in space bends and stretches under the influence of massive bodies and rapid motion. Understanding these effects is essential for deep-space missions, satellite navigation, and fundamental physics research. This article delves into how time behaves differently in the cosmos, exploring the interplay between gravity, speed, and the very fabric of spacetime.

The Physics of Relativity in the Cosmos

In the early 20th century, Einstein revolutionized our concept of time with his theory of relativity. According to special relativity, time is not absolute. Instead, it depends on an observer’s state of motion. When objects approach the speed of light, unusual effects like time dilation become significant.

Special Relativity and Moving Clocks

- As velocity increases, moving clocks tick more slowly relative to a stationary observer.

- This effect has been confirmed by flying precise atomic clocks on jets, which register fewer seconds than identical clocks on the ground.

- The famous twin paradox demonstrates how a twin traveling at high speed ages less than their earthbound sibling.

Although we rarely approach light speed on Earth, spacecraft traveling at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour still experience measurable shifts in onboard timekeeping instruments. Precise adjustments are required for mission planning and data synchronization.

Gravity and the Warping of Spacetime

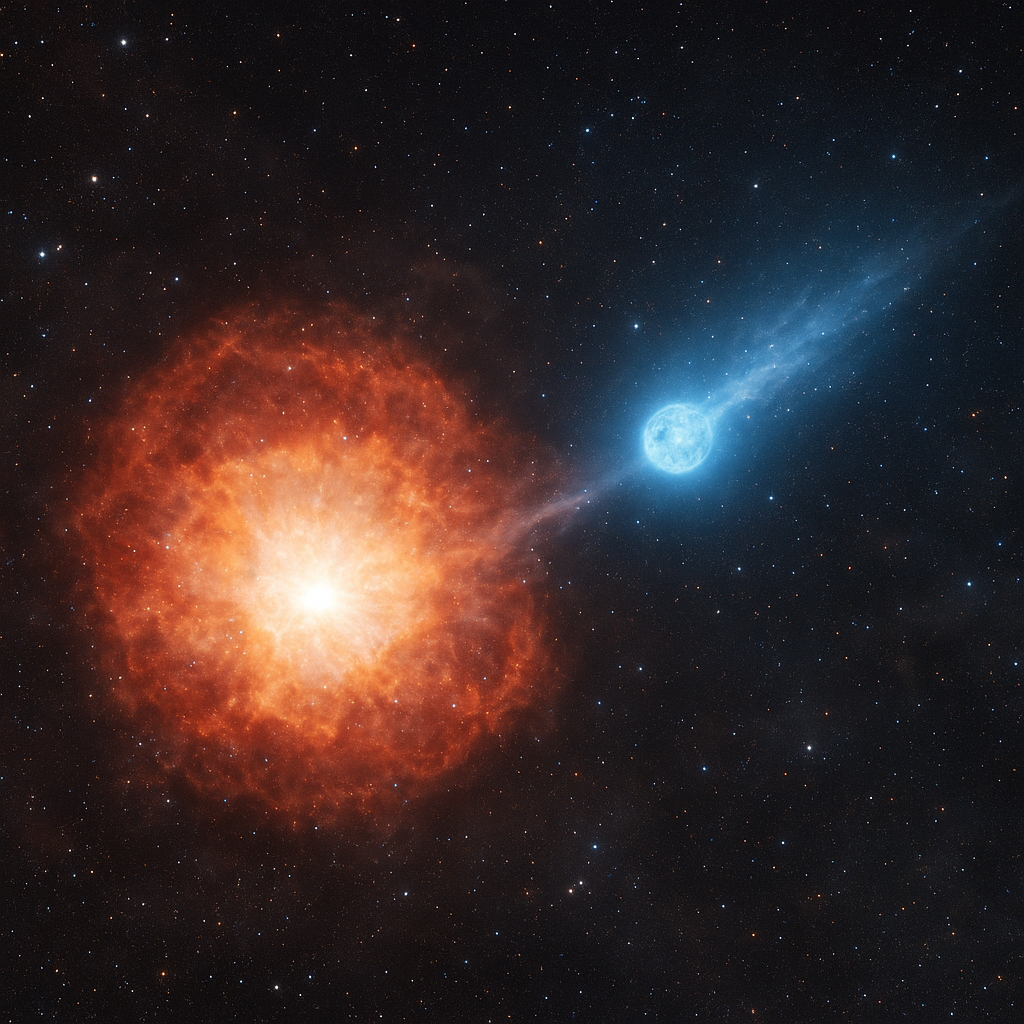

General relativity extends Einstein’s insights by showing that mass and energy warp the fabric of spacetime. This curvature affects how time flows in regions of varying gravitational strength. In effect, a clock closer to a massive object will tick more slowly than one farther away.

Gravitational Time Dilation

- Clocks at sea level run slower than clocks on a mountain peak due to Earth’s gravitational field.

- Near dense objects like neutron stars or black holes, time can slow dramatically, approaching a standstill at the event horizon.

- These differences have been validated through experiments involving satellites and ground-based atomic clocks.

For instance, Global Positioning System satellites orbiting some 20,000 kilometers above Earth must correct for both special and general relativistic effects. Without these adjustments, positional errors would accumulate by several kilometers each day.

Velocity Effects on Time Measurement

While gravity bends time by curving spacetime, direct motion through space also alters the ticking rate of clocks. Special relativity tells us that two observers in relative motion disagree on elapsed durations.

Practical Examples in Spaceflight

- Astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) travel at about 7.66 km/s, experiencing a slight slow-down of onboard clocks compared to Earth.

- High-precision experiments measure this tiny discrepancy, contributing to our understanding of velocity-induced time shifts.

- Long-duration missions to Mars will require even more exact synchronization to ensure communication and navigation systems operate flawlessly.

Understanding how velocity influences time allows engineers to design more reliable spacecraft systems and correct sensor data for time-dependent processes such as radiation monitoring or biological studies.

Practical Challenges for Spacefarers

For astronauts and mission controllers, accounting for relativistic time effects is more than an academic exercise. Accurate timekeeping underpins navigation, communication, and scientific measurements.

Synchronization Across Vast Distances

- Deep-space probes like Voyager and New Horizons rely on precise time stamps to relay scientific data back to Earth.

- Delays in signal reception, ranging from minutes to hours, must be factored into mission commands.

- Onboard systems use predictive models of gravity and motion to pre-adjust instrument schedules before sending data.

Astronauts conducting experiments on the ISS must also correct biological and physical observations for minute shifts in local time. Even a few microseconds of error can accumulate when measuring fast processes like particle interactions or atomic transitions.

Observing Time from Earth and Beyond

Earth-based observatories and space telescopes provide windows into extreme cosmic environments where time behaves in exotic ways.

- Pulsars, spinning neutron stars emitting regular beams of radiation, serve as natural cosmic clocks. Observing their pulses reveals time dilation near their immense gravitational fields.

- Gravitational lensing, where light bends around massive galaxies, offers indirect evidence of spacetime curvature and associated time delays.

- Future missions aim to place clocks in close orbit around black holes to directly probe the slow-down of time as predicted by general relativity.

These observations enrich our understanding of the cosmic tapestry and test the limits of current physical theories in the most extreme environments known to science.

Timekeeping Technologies for the Future

Advances in time measurement are crucial for exploring deeper reaches of space. Next-generation atomic and optical clocks promise unprecedented precision.

- Optical lattice clocks, with stability orders of magnitude beyond current models, will help map subtle variations in gravitational potential across the Solar System.

- Quantum sensors could detect minute distortions in spacetime from passing gravitational waves or dark matter interactions.

- Deploying these instruments on satellites or crewed missions will refine our models of how time flows under differing cosmic conditions.

As technology progresses, humanity will achieve ever more accurate chronometry, enhancing navigation for interplanetary travel and deepening our grasp of nature’s fundamental laws.