The cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation offers an unparalleled window into the infancy of our Universe. Generated roughly 380,000 years after the Big Bang, this faint glow permeates every direction of space. By studying its subtle variations in temperature and polarization, scientists have unlocked clues about the inflationary epoch, the distribution of dark matter, and the genesis of large-scale cosmic structures. Here we delve into the secrets hidden in CMB observations and explore how they reshape our understanding of the cosmos.

Origins and Discovery

In the mid-20th century, physicists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman predicted a relic radiation left over from the hot, dense early Universe. However, it was Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson’s serendipitous detection in 1965 that confirmed its existence. This radiation corresponds to a near-perfect blackbody spectrum at a temperature of 2.725 K, uniform to one part in 100,000. The discovery cemented the Big Bang theory as the leading cosmological model and opened a new era in observational cosmology.

Anisotropies and Temperature Fluctuations

Although remarkably uniform, the CMB exhibits minute anisotropies—tiny temperature differences across the sky—that carry imprints of primordial density variations. Satellite missions such as COBE, WMAP, and Planck have progressively refined our measurements, revealing a wealth of structure on angular scales from degrees to arcminutes.

- COBE (1992): First detection of large-scale anisotropies.

- WMAP (2003–2010): Mapped fluctuations down to 0.2° resolution, enabling precise estimates of cosmological parameters.

- Planck (2009–2013): Delivered high-resolution maps and polarization data, reducing uncertainties to sub-percent levels.

These temperature fluctuations directly reflect the seeds of galaxies and clusters. A rich harmonic pattern known as the acoustic peaks arises from oscillations in the primordial plasma. The locations and amplitudes of these peaks constrain the universe’s curvature, baryon density, and the nature of dark components.

Polarization Patterns and B-modes

Beyond temperature maps, CMB polarization has become a frontier in precision cosmology. Thomson scattering at recombination generates two polarization modes: E-modes (gradient-like) and B-modes (curl-like). While E-modes have been robustly measured, the hunt for primordial B-modes—signatures of gravitational waves from inflation—remains a golden objective.

- E-modes: Confirmed by both WMAP and Planck, matching theoretical predictions for scalar density perturbations.

- B-modes (lensing): Produced by gravitational lensing of E-modes by large-scale structures; observed by ground-based experiments.

- Primordial B-modes: A direct probe of high-energy physics in the first fractions of a second; current limits place the tensor-to-scalar ratio r < 0.06.

Detecting primordial B-modes would illuminate the energy scale of inflation, potentially at 10^16 GeV. Such a breakthrough would bridge cosmology with particle physics and shed light on mechanisms beyond the Standard Model.

Implications for Dark Matter and Dark Energy

The CMB’s acoustic peaks also inform us about elusive constituents: dark matter and dark energy. By fitting theoretical power spectra to observed anisotropies, researchers infer that ordinary baryonic matter constitutes only ~5% of the critical density, while dark matter accounts for ~27%, and dark energy ~68%.

- Cold Dark Matter: Non-relativistic particles shaping gravitational wells where galaxies form.

- Dark Energy: Driving the current accelerated expansion; characterized by its equation of state parameter w ≈ –1.

- Neutrino Masses: CMB data limits the sum of neutrino masses to below ~0.12 eV, influencing structure growth.

These insights unify independent observations—supernova luminosity distances, baryon acoustic oscillations, and galaxy surveys—into the standard ΛCDM framework, yet puzzles remain. The Hubble tension, for instance, arises from discrepant expansion rates measured locally versus inferred from the CMB.

Higher-Order Statistics and Non-Gaussianity

Standard analyses assume that primordial fluctuations are nearly Gaussian. However, slight deviations—termed non-Gaussianities—can reveal complex interactions during inflation. Advanced statistical tools probe three- and four-point correlation functions (bispectrum and trispectrum) in CMB maps. So far, results are consistent with minimal non-Gaussianity, but future surveys could uncover subtle signatures of multi-field inflation or exotic high-energy dynamics.

Foreground Contamination and Data Processing

Extracting pristine CMB signals demands meticulous separation of galactic and extragalactic foregrounds. Synchrotron emission, thermal dust, and free–free radiation overlay the sky in multiple frequency bands. Component separation algorithms—Internal Linear Combination, Needlet Independent Component Analysis, and Bayesian frameworks—disentangle these contributions. Accurate foreground removal is paramount for robust detection of weak B-mode polarization and small-scale anisotropies.

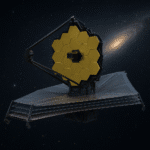

Future Missions and Technologies

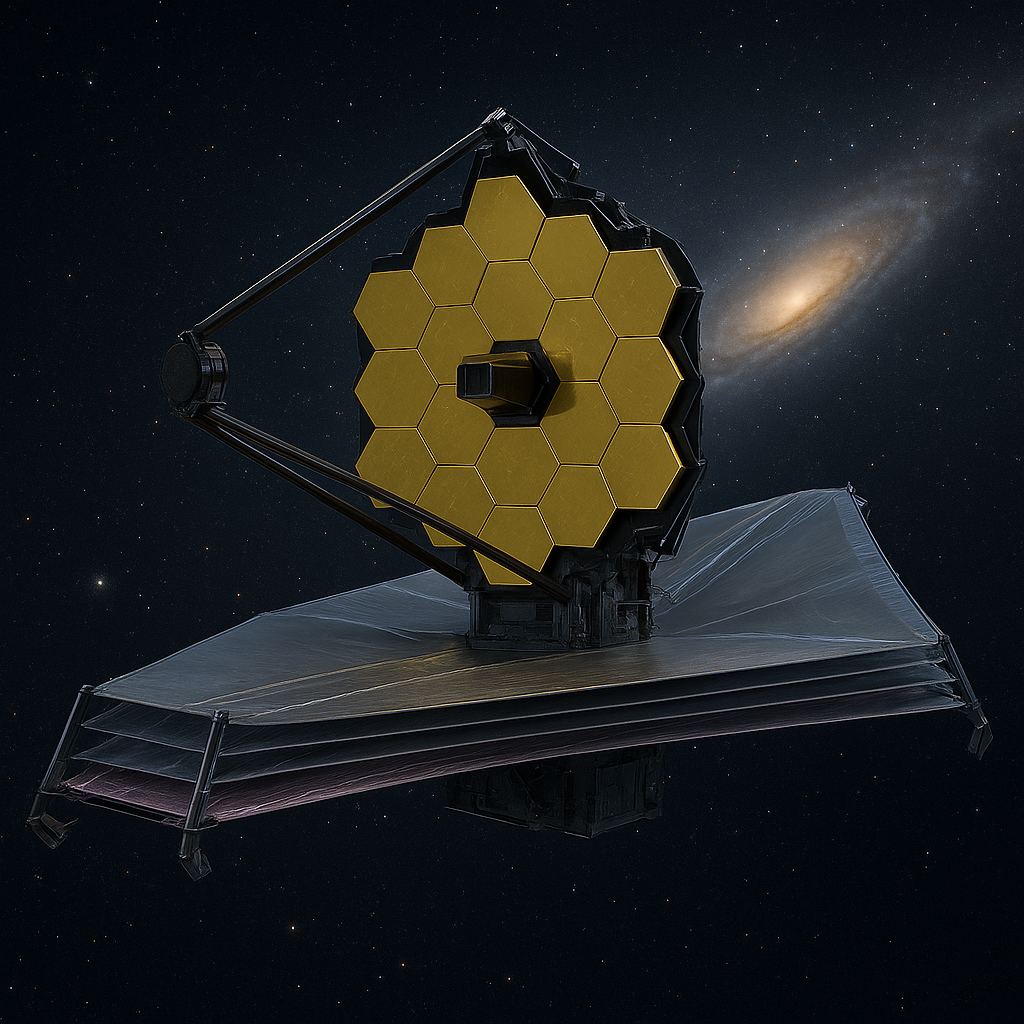

Looking ahead, upcoming experiments promise unprecedented sensitivity. Ground-based telescopes like the Simons Observatory and CMB-S4 aim to map polarization over wide sky areas with colour channels from 30 to 300 GHz. Meanwhile, satellite proposals such as LiteBIRD and PICO target full-sky coverage optimized for primordial B-modes.

- Simons Observatory: Consists of large and small aperture telescopes in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

- CMB-S4: A coordinated global effort to push sensitivity by an order of magnitude.

- LiteBIRD: A JAXA-led mission designed for large-scale polarization measurement.

Innovations in detector technology—transition-edge sensors and kinetic inductance detectors—will drive these advances. Improved control of systematic errors and advanced analysis pipelines will enable exploration of physics at energies far beyond terrestrial colliders.

Connecting to Large-Scale Structure

The interplay between CMB and large-scale structure surveys amplifies cosmological tests. Cross-correlating CMB lensing maps with galaxy catalogs reveals the growth history of matter clustering, testing gravity on cosmic scales. Such synergies also constrain the sum of neutrino masses and possible interactions within the dark sector.

Conclusion Through Ongoing Discovery

Cosmic microwave background radiation remains an extraordinary tool for unraveling the early Universe’s mysteries. Each improvement in measurement precision unveils layers of depth—from acoustic oscillations to subtle polarization patterns. As new missions come online, we anticipate breakthroughs on the Planck horizon, offering fresh insights into the nature of space, time, and fundamental physics.