Detecting distant planets and unveiling the properties of their atmospheres represents one of the most exciting frontiers in modern astronomy. As telescopes and analytical techniques have become more sophisticated, researchers no longer limit themselves to finding new worlds; they probe the gaseous envelopes that cloak these exoplanets. Learning to decode the faint signals that reach Earth empowers scientists to determine chemical composition, thermal structure, and potential signs of habitability. This article explores the primary methods used to detect and characterize planetary atmospheres, from detailed spectroscopy to innovative imaging strategies, and highlights upcoming missions poised to transform our understanding.

Observational Techniques for Atmospheric Detection

Astronomers employ several complementary approaches to sense the presence of an atmosphere around a remote world. The most widely used relies on observing transits, when an exoplanet crosses its host star’s disk, causing a minute dip in brightness. This photometric signature can reveal not only the planet’s size but, through careful analysis of the light filtered by its atmosphere, also the absorption at different wavelengths. Secondary eclipses, when the planet slips behind the star, enable measurement of emitted or reflected light, isolating the contribution of the atmosphere from stellar glare. Phase curve observations sample the changing brightness over an orbit, mapping temperature variations and cloud patterns.

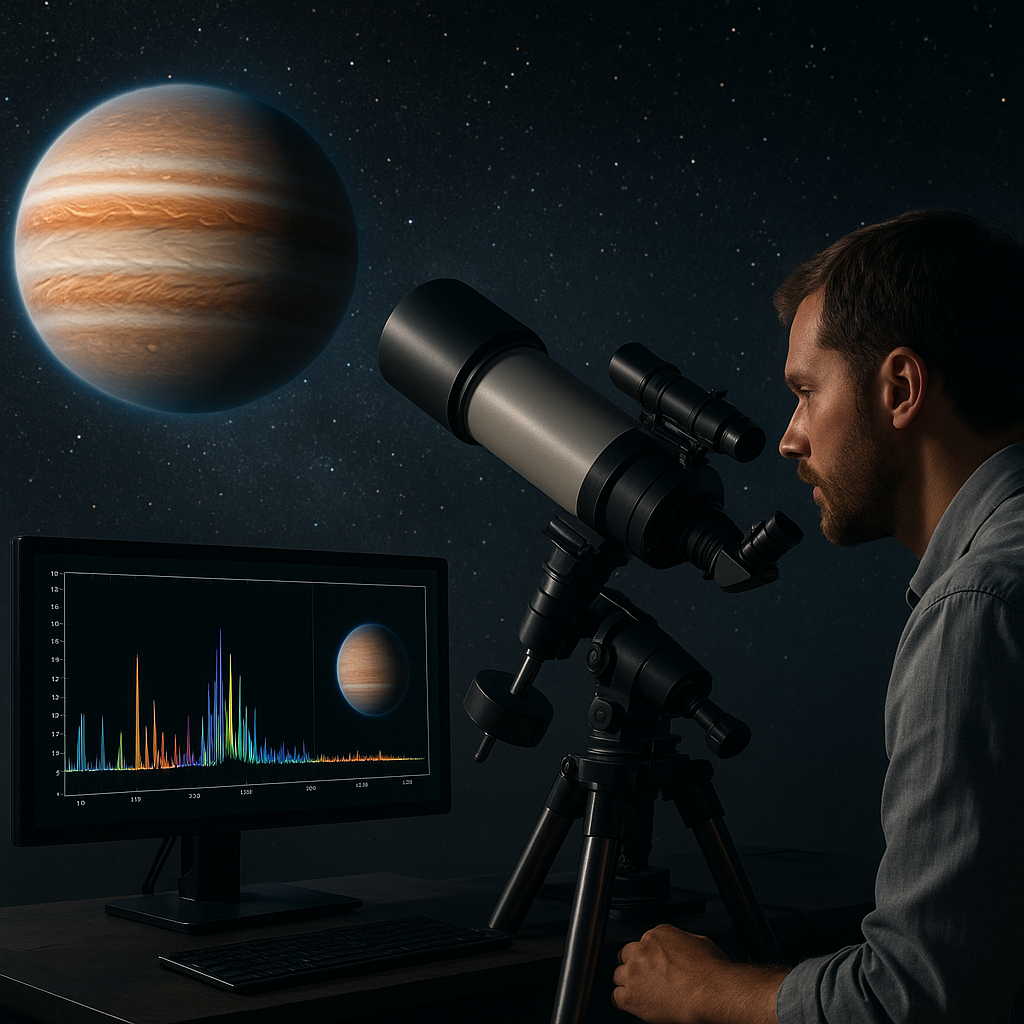

In radial velocity surveys, shifts in stellar spectral lines betray the gravitational tug of an unseen planet. When combined with transit data, this technique yields planetary mass and radius, and therefore bulk density—a critical parameter for assessing whether a world harbors a gaseous envelope or is predominantly rocky. High-resolution spectrographs on ground-based telescopes also detect atmospheric absorption lines moving at the planet’s orbital velocity, distinguishing them from stationary telluric features.

- Transit photometry measures lightcurves during planetary passages.

- Secondary eclipse photometry isolates planetary flux.

- High-resolution Doppler spectroscopy tracks shifting molecular lines.

- Direct imaging captures photons emitted or reflected by the planet itself.

Each technique demands exceptional instrumental stability and calibration. Ground-based observatories must correct for atmospheric turbulence, scattering, and absorption, while space-based platforms eliminate many of those challenges but face limitations in mirror size and instrument lifespan.

Spectroscopy: Unlocking Chemical Composition

Transmission Spectroscopy

When starlight filters through a planet’s limb, molecules in the atmosphere absorb specific wavelengths, imprinting dark lines on the stellar spectrum. By comparing in-transit and out-of-transit spectra, astronomers extract an absorption spectrum that reveals molecular signatures of water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, and exotic species like titanium oxide. Modern instruments such as the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) deliver high-precision measurements in the infrared, where many key absorption bands lie.

Retrieval algorithms invert these spectra, fitting line depths and shapes to derive temperature–pressure profiles and abundances. Complex radiative transfer models account for scattering by clouds and aerosols. Challenges include separating stellar activity—spots and faculae—from genuine atmospheric features, and achieving sufficient signal-to-noise in faint systems orbiting dim or distant stars.

Emission and Reflection Spectroscopy

During secondary eclipses, a planet’s thermal emission and reflected light are momentarily blocked, causing a subtle drop in total flux. Measuring the depth of this dip at various wavelengths yields an emission spectrum that constrains dayside temperatures and albedo. For hot Jupiters, brightness temperatures in the infrared can exceed 2000 K, offering insights into heat redistribution by winds and potential thermal inversions.

Reflection spectroscopy, though even more challenging, probes scattered starlight in the optical range. It can inform on cloud top properties and surface compositions for cooler planets. Instruments like CHEOPS, TESS, and PLATO aim to expand reflection measurements to smaller and more temperate worlds.

Direct Imaging and High-Contrast Methods

By blocking or suppressing a star’s overwhelming glare, direct imaging captures light emitted or reflected by an exoplanet itself. Coronagraphs and starshades, combined with extreme adaptive optics, achieve contrasts exceeding one part in a billion. This approach excels for widely separated, young, self-luminous gas giants whose thermal emission remains detectable in the near-infrared.

Facilities such as the Gemini Planet Imager and SPHERE on the Very Large Telescope exploit deformable mirrors and precise wavefront control to correct atmospheric distortions. Imaging surveys have revealed dozens of massive planets at orbital distances beyond 10 AU. Spectroscopic follow-up of these direct detections yields spectra with broad molecular bands, offering a direct probe of infrared emission and enabling measurements of effective temperature and gravity.

- Coronagraphic suppression to mask stellar light.

- Adaptive optics for real-time atmospheric correction.

- Integral field spectrographs for simultaneous spatial and spectral data.

While direct imaging struggles with close-in or Earth-size worlds, planned upgrades to ground-based Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs) promise inner working angles small enough to image temperate planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars.

Future Prospects and Next-Generation Missions

Advances on the horizon will enhance sensitivity, resolution, and spectral coverage. The James Webb Space Telescope, launching soon, offers unprecedented infrared performance, expected to detect trace gases in warm Neptunes and possibly rocky planets. The ARIEL mission, dedicated to atmospheric spectroscopy, will survey hundreds of exoplanets to establish population-level trends in composition and climate. Large ground-based ELTs like GMT, TMT, and ESO’s ELT will incorporate high-dispersion spectrographs and extreme adaptive optics to pursue high-contrast imaging at finer scales.

Concepts for future flagships—HabEx and LUVOIR—envision space-based telescopes with apertures exceeding four meters, equipped with advanced coronagraphs and starshades. These observatories aim to directly image Earth analogs around Sun-like stars, obtaining reflection spectra in the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared. Such data would reveal potential biosignature gases—oxygen, ozone, methane—in concert with habitability indicators like surface water clouds.

- space-based observatories eliminate atmospheric interference and expand wavelength access.

- High-dispersion spectroscopy combined with high-contrast imaging yields robust detections even in challenging systems.

- Machine learning techniques accelerate atmospheric retrieval by exploring vast parameter spaces more efficiently.

As observational techniques evolve, so too do theoretical and computational models. Improved line lists, 3D climate simulations, and global circulation models help interpret complex datasets. Ultimately, the synergy between cutting-edge instrumentation, novel data analysis, and ambitious space missions promises to transform our view of distant worlds—revealing the diversity of planetary atmospheres and inching us closer to identifying true Earth analogs beyond our solar system.