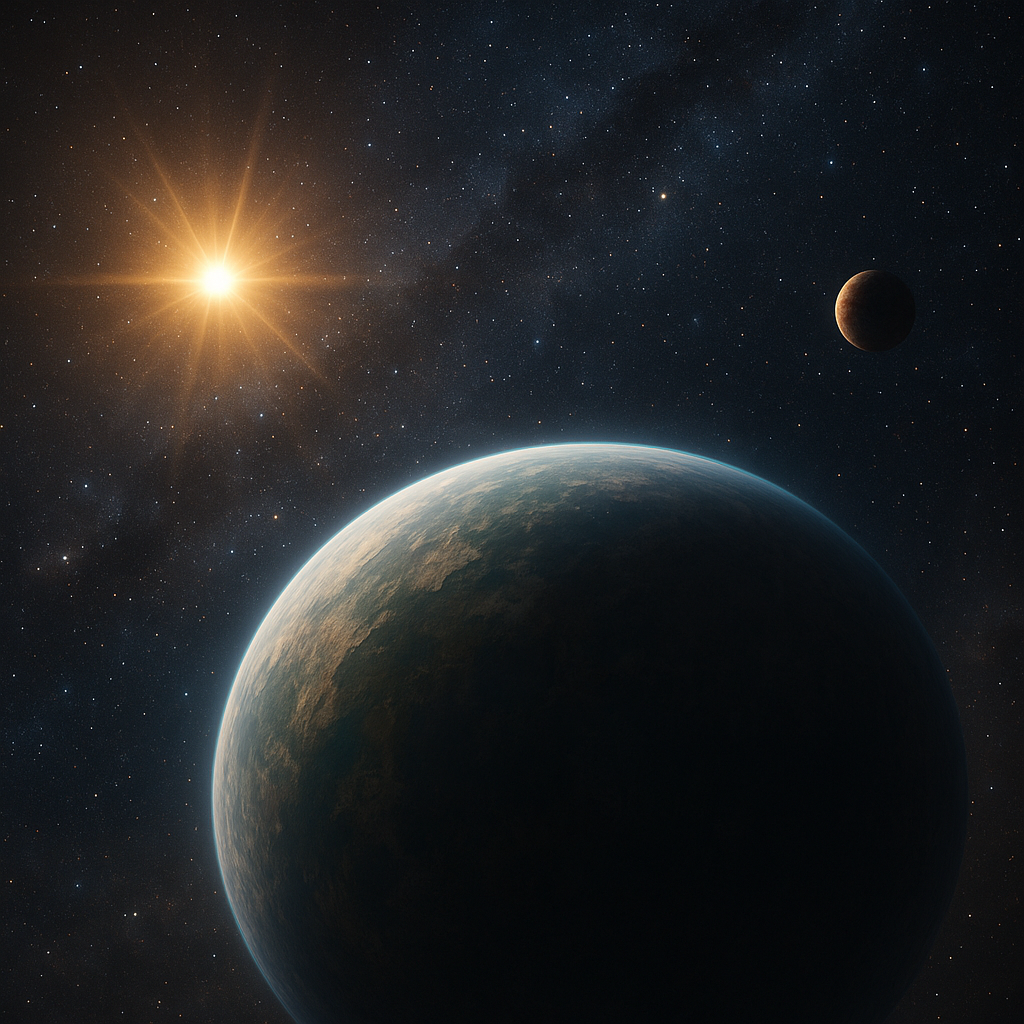

The quest to identify worlds beyond our solar system that could support life has driven astronomers and researchers to push the limits of technology and imagination. By studying the diverse population of exoplanets, scientists aim to unravel the mysteries of planetary habitability and the conditions necessary for life to emerge. From distant gas giants to rocky Earth analogues, each discovery brings us closer to answering one of humanity’s most profound questions: Are we alone in the cosmos?

Understanding Exoplanets and Their Environments

The term exoplanet refers to any planet orbiting a star outside our solar system. Since the first confirmed detection in 1992, over 5,000 worlds have been cataloged, revealing an astonishing variety in size, composition, and orbital dynamics. Some of these distant worlds are massive gas giants akin to Jupiter, while others are small, rocky bodies that may resemble our own planet.

Key to evaluating these distant worlds is examining their atmosphere, which can provide clues about temperature, pressure, and chemical makeup. For example, a thick envelope rich in carbon dioxide may lead to a runaway greenhouse effect, rendering a planet inhospitable. Conversely, the presence of nitrogen, oxygen, or traces of methane might hint at processes—possibly even biological activity—that maintain a stable climate.

Another crucial factor is the planet’s position relative to its star. This region, often dubbed the Goldilocks Zone, is where temperatures allow liquid water to exist on the surface. Too close, and the world becomes scorched by intense stellar radiation; too far, and it freezes into a barren iceball. Understanding the interplay between stellar luminosity, planetary reflectivity, and orbital eccentricity is essential for assessing whether a given exoplanet can sustain habitable conditions over geological timescales.

Technological Advances in Exoplanet Detection

The rapid growth in exoplanet science stems from breakthroughs in observational techniques. Early efforts relied on the radial velocity method, measuring the wobble of a star induced by gravitational pulls from orbiting planets. Later, the transit technique—monitoring the slight dimming of starlight as a planet crosses in front of its host—revolutionized the field by enabling the detection of thousands of new candidates.

Spaceborne Observatories

- Kepler Space Telescope: Launched in 2009, Kepler surveyed a single star field for four years, discovering over 2,600 confirmed exoplanets. Its legacy lies in the statistical understanding of planet frequencies.

- Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS): Building on Kepler’s success, TESS scans nearly the entire sky, focusing on bright, nearby stars to facilitate follow-up observations.

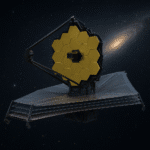

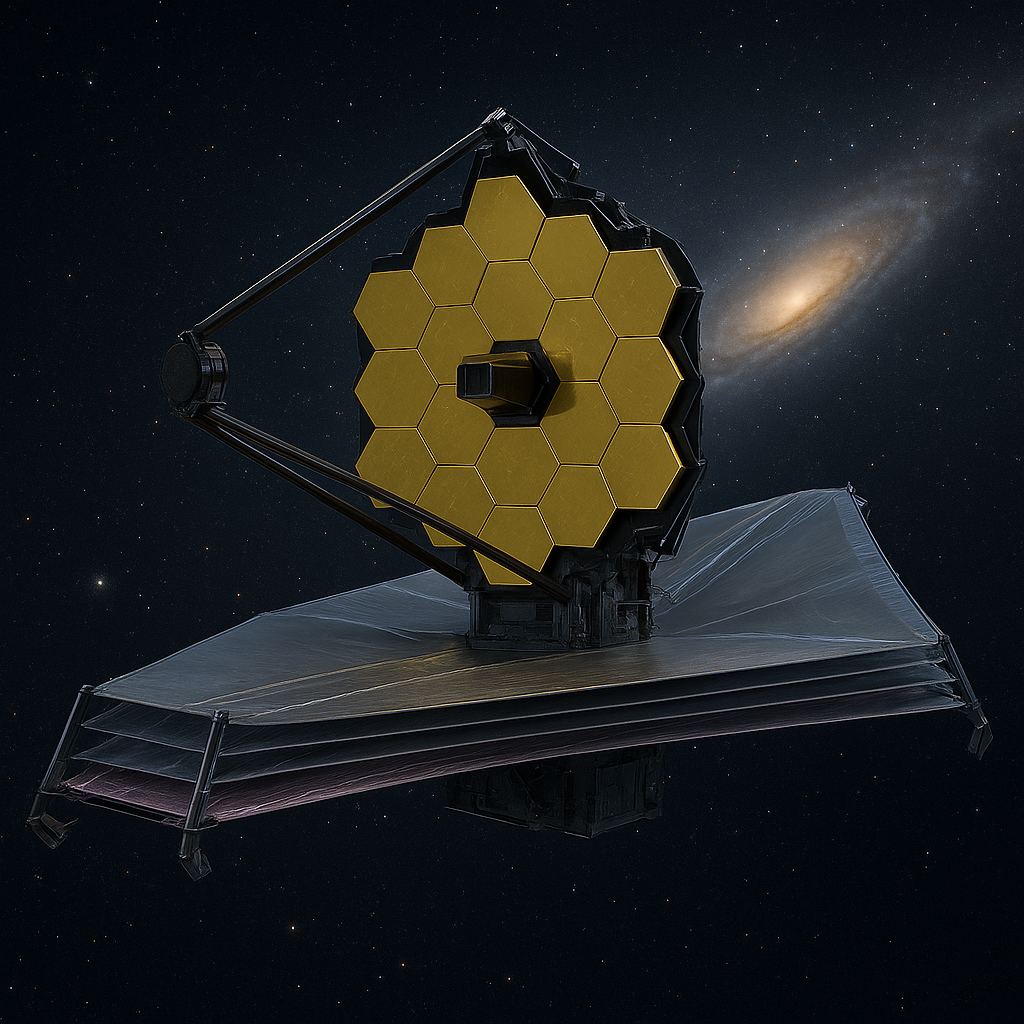

- James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): With unprecedented infrared sensitivity, JWST promises to probe the atmospheres of small, rocky exoplanets, searching for key molecular fingerprints.

On the ground, next-generation observatories equipped with advanced adaptive optics, such as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), aim to directly image exoplanets by blocking out starlight. Combined with high-resolution spectroscopy, these facilities will dissect atmospheric composition, weather patterns, and even surface features, heralding a new era of detailed characterization.

Assessing Habitability: Criteria and Challenges

Determining whether an exoplanet can host life involves assessing a complex matrix of factors:

- Stellar Type and Activity: Cool, stable stars like K-dwarfs offer long-lived energy output but may exhibit flares that strip planetary atmospheres.

- Planetary Mass and Composition: A minimum mass is required to retain an atmosphere, while excessive gravity can generate heavy, unbreathable envelopes.

- Orbital Stability: Highly eccentric orbits risk extreme temperature swings, challenging climate stability and the persistence of liquid water.

- Atmospheric Chemistry: The presence of biosignatures such as oxygen, ozone, or methane in specific ratios could indicate biological processes.

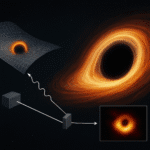

However, interpreting potential biosignatures is fraught with ambiguity. Abiotic mechanisms can mimic biological signals, necessitating multi-wavelength observations and contextual information about planetary geology and stellar radiation. Researchers in the field of astrobiology develop models to distinguish false positives from genuine signs of life, emphasizing the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration between astronomers, geologists, chemists, and biologists.

Additionally, tidal locking—a scenario where one hemisphere perpetually faces the star—can create extreme climate gradients. While the dayside may become inhospitable, the terminator region could harbor temperate conditions. Simulating such climates demands sophisticated three-dimensional models that couple atmospheric dynamics with surface processes.

Emerging Frontiers in Exoplanet Exploration

The next decade promises transformative missions and instruments poised to deepen our understanding of habitable worlds. Proposed space telescopes like the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx) and the Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor (LUVOIR) aim to directly image Earth-sized planets around Sun-like stars, searching for the faint glimmer of reflected light. On the ground, networks of smaller telescopes will complement these flagship missions, monitoring transit windows and providing rapid follow-up.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are revolutionizing data analysis pipelines, sifting through vast datasets to identify subtle planetary signals buried in noise. These techniques also assist in modeling complex atmospheric chemistry and predicting optimal observation strategies, enhancing the efficiency of resource allocation.

The integration of citizen science initiatives further accelerates discovery. Platforms such as Planet Hunters invite the public to examine light curves for potential transits, tapping into collective human pattern recognition. This crowdsourced approach has already yielded several surprising finds, demonstrating the power of community involvement.

As our observational toolkit expands, so too does the possibility of finding truly Earth-like exoplanets. Each new detection refines our estimates of how common habitable worlds may be in the galaxy. With perseverance, innovation, and a spirit of exploration, the search for life beyond Earth enters a golden age—one in which humanity edges ever closer to answering the eternal question of whether we share the universe with other living beings.