The first glimpse into the heart of a galaxy, where light itself is trapped by gravity, marked a milestone in modern astronomy. Through international collaboration and cutting-edge technology, scientists produced the very first image of a black hole, opening a window into realms once deemed beyond human reach. This exploration not only pushes the boundaries of physics but also challenges our understanding of the universe’s most mysterious objects.

The Quest for the Dark Giants

For decades, astronomers have suspected that at the cores of many galaxies lie supermassive black holes weighing millions to billions of times the mass of our Sun. Despite their immense mass, these objects emit no direct light. Their presence was inferred from the motion of nearby stars and the powerful jets of energetic particles that sometimes spew from galactic centers.

Key milestones in this quest include:

- Detection of stellar orbits in the Milky Way’s center, pointing to a compact object millions of times more massive than the Sun.

- Observations of high-speed gas clouds swirling around active galactic nuclei.

- Radio and X-ray imaging of jets launched at nearly the speed of light.

These indirect methods laid the groundwork, but capturing a direct image demanded revolutionary techniques to resolve details smaller than our solar system across millions of light-years.

Techniques of Cosmic Imaging

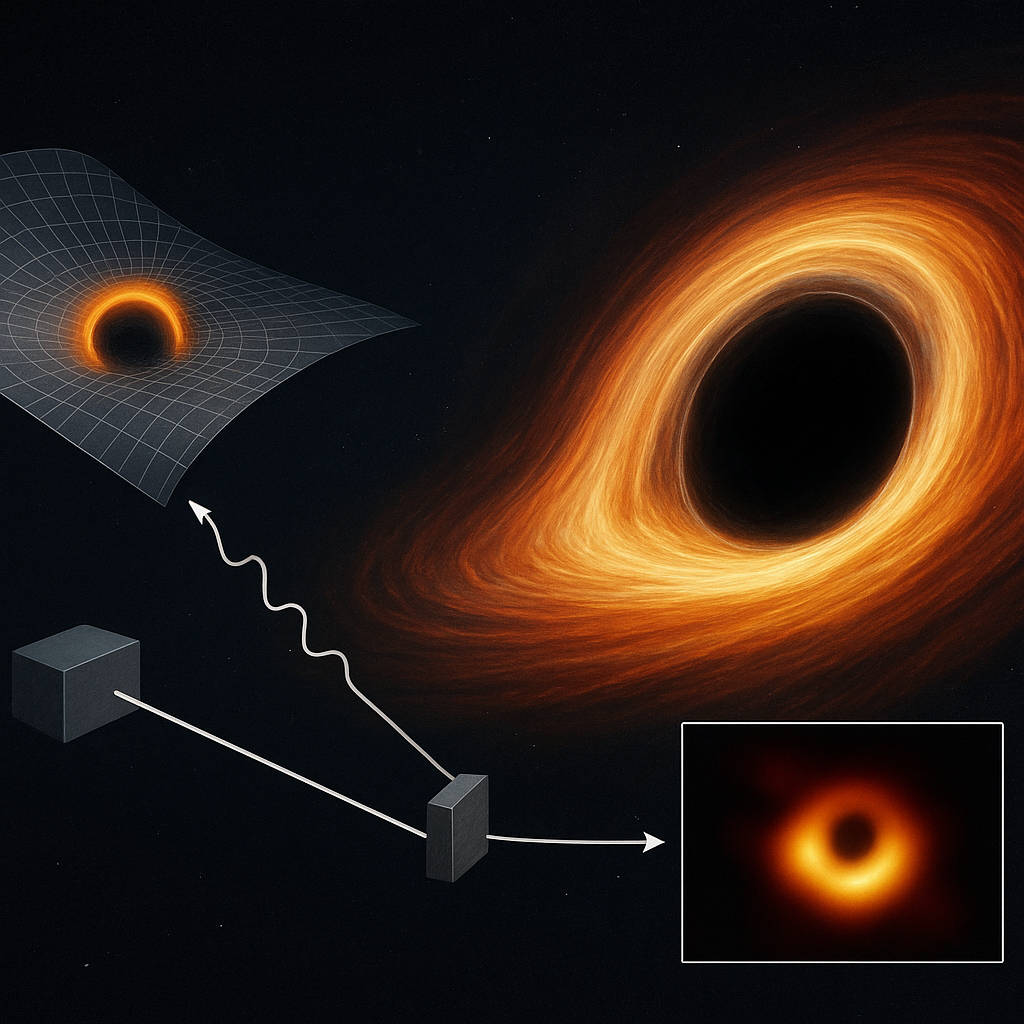

Imaging a black hole requires overcoming two fundamental challenges: the object’s incredibly small angular size on the sky and its location within dusty, turbulent environments. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) addressed these by linking radio dishes around the globe into an Earth-sized virtual telescope, achieving unprecedented resolution. This technique is known as very long baseline interferometry (VLBI).

- Global Array: Combining data from multiple radio observatories spanning continents, effectively creating a telescope the size of Earth.

- High-Frequency Observations: Using millimeter-wave wavelength bands to minimize atmospheric distortion and penetrate interstellar dust.

- Time Synchronization: Employing atomic clocks at each station to align data streams with sub-nanosecond precision.

- Correlation Processing: Merging petabytes of raw signals to reconstruct the target’s image through complex Fourier transforms.

- Machine Learning Enhancements: Applying advanced algorithms to improve image clarity and reduce noise.

By coordinating telescopes from Hawaii to Europe, scientists achieved the first-ever view of a glowing ring surrounding a dark interior—an unmistakable signature of the event horizon, where gravity becomes so intense that not even light can escape.

Interpreting the Invisible

The EHT’s image reveals a bright crescent encircling a darker region known as the black hole’s shadow. This shadow is roughly 2.5 times larger than the actual photon ring, where photons orbit the black hole multiple times before escaping or falling in. The asymmetry in brightness arises from relativistic effects:

- Doppler Boosting: Material moving toward us appears brighter; receding gas dims.

- Gravitational Lensing: Light paths warp around the black hole, magnifying the ring.

- Time Dilation: Processes near the horizon slow down, affecting observed emission patterns.

The glowing structure itself is the hot accretion disk, composed of plasma spiraling inward. As gas heats up to billions of degrees, it emits synchrotron radiation detectable at radio frequencies. By measuring intensity and polarization across the disk, researchers infer magnetic field structures that drive jet formation and regulate accretion dynamics.

The Role of Simulation and Theory

High-fidelity simulations are crucial for interpreting observational data. Numerical models of magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) predict how magnetic fields interact with infalling matter. By comparing simulated images with real observations, scientists test the predictions of general relativity under extreme conditions. This synergy between theory and observation:

- Validates the shape and size of the event horizon as predicted by Einstein’s equations.

- Constrains the spin of the black hole, a key parameter influencing jet power and structure.

- Explores alternative gravity theories by checking for subtle deviations in the shadow shape.

Next Steps in Cosmic Exploration

With a proof of concept firmly established, the EHT collaboration plans to enhance the array’s capabilities. Future goals include:

- Adding more telescopes in strategic locations to improve image fidelity and dynamic range.

- Observing at shorter wavelengths for sharper views of the innermost regions.

- Increasing temporal resolution to capture dynamical changes in the accretion flow over minutes to hours.

- Extending observations to additional black holes, including the one at the center of our galaxy, Sagittarius A*.

These advancements promise to reveal how black holes lurk and grow, how they launch relativistic jets, and ultimately, how they shape the evolution of galaxies. Each new image brings us closer to deciphering the most powerful forces at play in the cosmos.