The endeavor to reshape the environments of other planets brings into sharp focus questions of responsibility, risk, and the very essence of what it means to be stewards of the cosmos. Terraforming—modifying an alien world’s atmosphere, temperature, or ecology to resemble Earth’s—has long captured the imagination of scientists and storytellers alike. Yet before setting foot on a terraformed plain, we must grapple with profound **ethical** considerations that span ecological, political, and philosophical realms. This article explores the multifaceted arguments surrounding the **responsibility** humanity bears when intervening in extraterrestrial ecosystems.

The Moral Imperative and Potential Risks

At the heart of the debate lies the tension between a **long-term** vision for humanity’s expansion and the immediate potential for catastrophic mistakes. Proponents of terraforming argue that the sheer scale of the universe demands we spread life beyond Earth, ensuring our species’ survival in the face of cosmic hazards such as asteroid impacts or supernovae. This view sees a moral **obligation** to preserve life by creating new habitats. Opponents counter that our track record of environmental mismanagement at home does not inspire confidence in our ability to handle planetary-scale engineering elsewhere.

Balancing Expansion and Caution

- Precautionary Principle: Insists on avoiding actions with unknown or irreversible consequences until their effects are well understood.

- Existential Risk Mitigation: Posits that spreading civilization reduces the chance of total annihilation by concentrating populations across multiple worlds.

- Irreversible Change: Highlights that altering a planet’s atmosphere or geology may permanently preclude its original state or any native life.

We must ask whether humanity’s desire to secure its future justifies taking bold steps with an **unknown** payoff. Every geoengineering experiment on Earth reminds us that well-intentioned projects can spiral into unintended disasters, from altered weather patterns to ecological collapse. The margin for error on a world like Mars or Venus might be slimmer still.

Ecological Considerations in Terraforming

The question of whether extraterrestrial bodies host indigenous microbial or prebiotic life remains open. Discovering even the simplest organisms would dramatically shift the ethical landscape, forcing us to confront the potential for **biodiversity** beyond Earth. Should the presence of native life forms impose an absolute barrier to terraforming? Or could a balanced approach allow coexistence between introduced Earth species and alien microbes?

Planetary Protection

- Preventing forward contamination is central to current space missions. Introducing Earth organisms could obliterate nascent ecosystems.

- Reverse contamination—returning extraterrestrial life to Earth—also poses unknown health and ecological threats.

- Strict protocols aim to preserve scientific integrity and avoid compromising potential habitats for indigenous life.

Even in the absence of detectable life, a planet’s intrinsic value may call for preservation. The concept of stewardship extends beyond living organisms to include geological features, mineral diversity, and atmospheric phenomena. Planetary environments may have unique processes that warrant noninterference. Advocates for minimal intervention emphasize the importance of studying pristine alien landscapes to expand our scientific understanding.

Governance, Ownership, and International Law

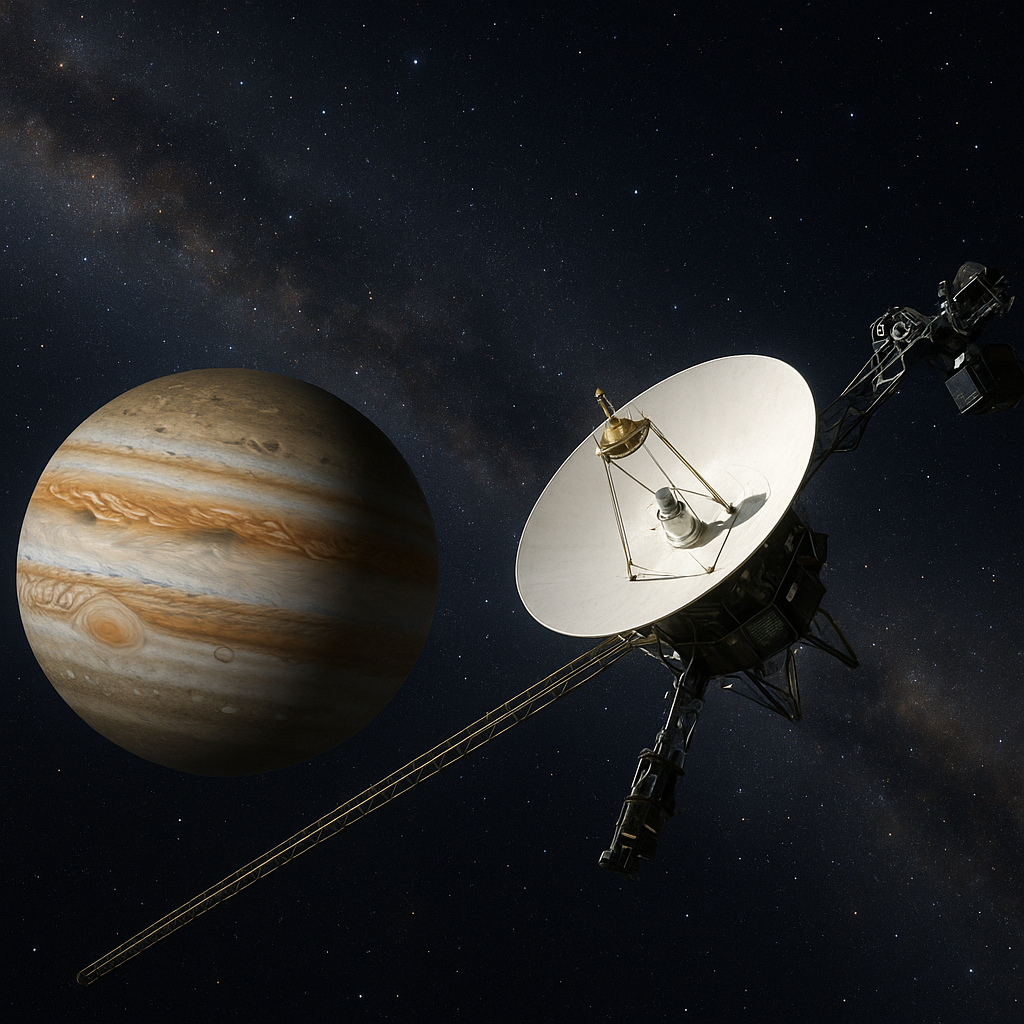

Terraforming raises pressing questions about governance: Who decides what transformations are permissible? Under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, celestial bodies are the “province of all mankind,” and no nation can claim sovereignty. Yet this framework lacks clear enforcement mechanisms and guidelines for large-scale environmental manipulation.

Possible Governance Models

- Global Consortium: A coalition of nations and private entities operating under transparent rules to oversee terraforming projects.

- Planetary Trust: Establishing an independent body to manage each world’s environment, with veto power to halt harmful practices.

- Free Market Approach: Allowing companies to spearhead terraforming efforts with limited regulation, raising concerns about exploitation and conflict.

Legal scholars propose filling treaty gaps with additional agreements on environmental standards, liability for accidents, and equitable resource sharing. Any robust regime must address questions of **autonomy** for future settlers: Will they inherit the right to transform their world further? How will conflicting visions for a planet’s use be reconciled?

Philosophical and Cultural Implications

Beyond politics and science, terraforming forces us to reflect on humanity’s relationship to nature and the cosmos. Are we rightful gardeners, empowered to cultivate barren worlds, or arrogant conquerors destined to repeat Earth’s mistakes? This debate touches on deep philosophical ideas about intrinsic versus instrumental value.

Intrinsic Value

- Affirms that environments possess worth independent of human use or enjoyment.

- Supports strict noninterference to preserve the alien world’s unique character.

Instrumental Value

- Views planets primarily as resources or potential habitats for human flourishing.

- Allows for transformation as a means to ensure survival and expand knowledge.

Culture and art will undoubtedly evolve in terraformed societies. Human narratives shaped by alien skies, modified landscapes, and hybrid ecosystems may foster new philosophies and worldviews. Yet the first settlers will carry the weight of history—the legacy of colonialism, environmental injustice, and social conflict. A conscious effort to learn from Earth’s past could guide the creation of more just and **sustainable** communities.

Technological Challenges and Ethical Responsibility

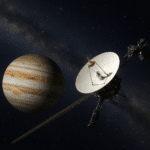

The mechanics of terraforming—greenhouse gas release, solar mirrors, bioengineered organisms—are daunting. Each technique brings unique risks: runaway warming, planetary contamination, or unforeseen feedback loops. Ethical decision-making must keep pace with technological advances, establishing oversight before irreversible steps are taken.

- Geoengineering Ethics: Ensuring that climate control strategies on one planet do not generate harmful cross-boundary effects on neighboring celestial bodies.

- Biocontrol Safety: Engineering microbes or plants for harsh environments without creating invasive species that outcompete hypothetical native life.

- Adaptive Management: Embracing flexible governance that can respond to new data, shifting public values, and emerging risks.

The principle of intergenerational **responsibility** underscores every decision. Actions taken today will shape the environmental legacy inherited by countless generations—and possibly by non-human life forms yet to emerge. In this light, prudence and humility must temper ambition.

Final Reflections

The ethics of terraforming revolve around reconciling humanity’s aspirations with its duty to prevent harm. As our technological prowess grows, so too must our ethical frameworks. Whether we ultimately choose to transform other worlds or preserve them in their untouched state, the debate will define our species’ character and our place in the universe.