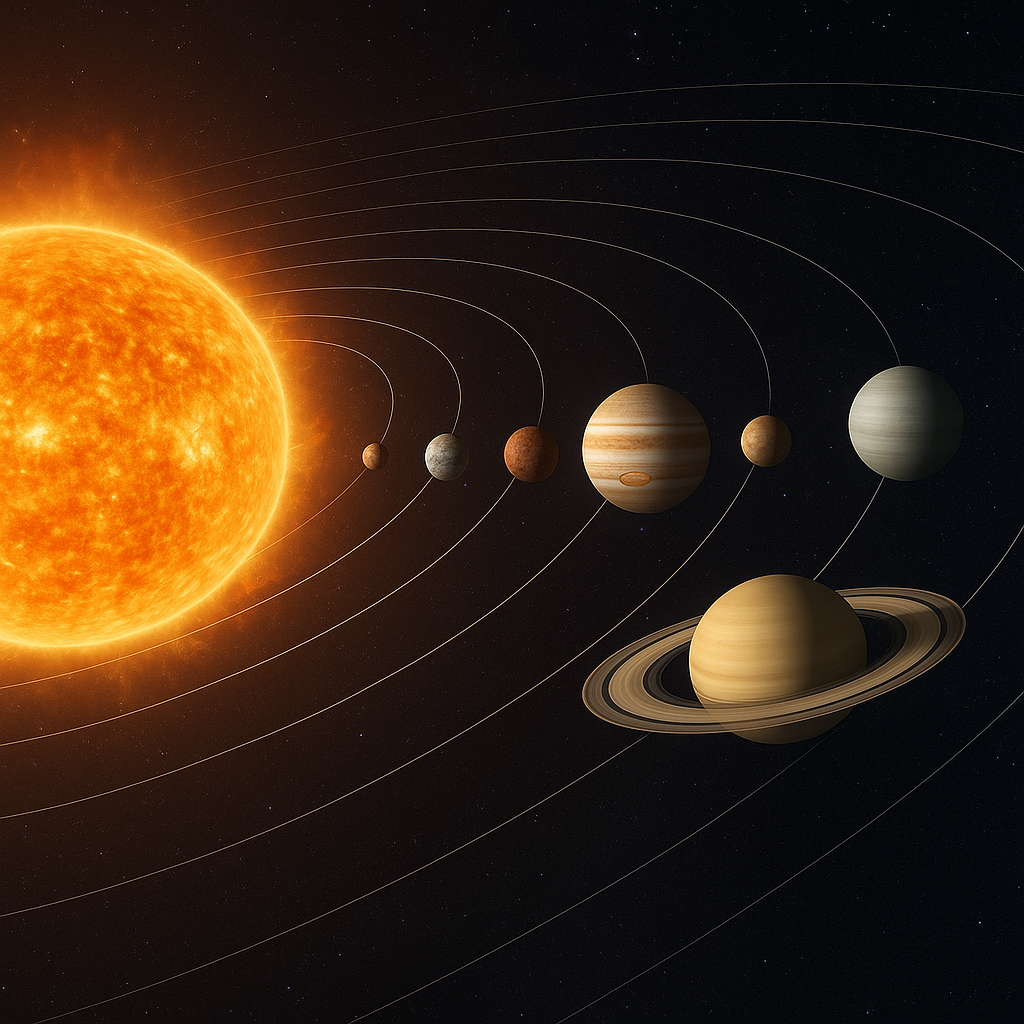

The Sun is not merely a glowing orb in the sky but the dynamic heart of our cosmic neighborhood. Its immense influence extends far beyond its visible surface, sculpting the very structure and behavior of the Solar System. From the swirling clouds of the early protoplanetary disk to the fragile atmospheres of distant worlds, the Sun’s forces—gravitational, magnetic, and radiative—dictate the fates of planets, comets, and asteroids alike.

Solar Genesis and Protoplanetary Disk

In the earliest epoch of our system’s history, a giant molecular cloud collapsed under the pull of gravity, triggering the birth of a young star. This infant Sun, shrouded in dust and gas, spun rapidly and ejected material into a flattened protoplanetary disk. It was within this rotating disk that planetesimals coalesced and planetary embryos took shape.

Disk Composition and Temperature Gradients

- Inner disk regions reached temperatures above 1,000 K, enabling only refractory materials like silicates and metals to condense.

- Beyond the “frost line,” volatile ices of water, methane, and ammonia solidified, allowing gas giants to amass massive envelopes of hydrogen and helium.

- Pressure and shock waves, driven by the Sun’s early outbursts, created zones of enhanced density that served as cradles for planetary formation.

Radiation Pressure and Disk Clearing

As fusion ignited in the Sun’s core, intense radiation pressure and stellar winds gradually blew away residual gas and dust. This process, spanning a few tens of millions of years, cleared the disk and halted further planetary growth. Leftover fragments became asteroids in the inner regions and comets in the outer reaches.

Interior Dynamics and Energy Production

The Sun’s capacity to influence its surroundings stems from the powerful processes at its core and the layers that transmit energy outward. Understanding these layers reveals how energy generation and transport determine the Sun’s observable properties and its interactions with space.

Core and Nuclear Fusion

At the heart of the Sun, temperatures soar beyond 15 million K, initiating the proton–proton chain reaction. Here, hydrogen nuclei fuse into helium, releasing gamma rays and neutrinos. This photosphere energy eventually emerges as visible light after wandering through the radiative and convective zones.

Radiative and Convective Zones

- Radiative Zone: Photons randomly scatter through ionized gas, a journey that can take hundreds of thousands of years before reaching the outer layers.

- Convective Zone: Hot plasma rises, cools at the surface, and plunges back down, creating the granulation patterns observed on the solar surface.

Photosphere, Chromosphere, and Corona

The photosphere represents the bright surface we see, with temperatures around 5,800 K. Above it lies the chromosphere, where spicules and flares originate, and beyond that, the corona—a tenuous plasma heated to over a million K by magnetic reconnection events.

Solar Magnetic Field

- Globally organized as a dipole, but highly dynamic due to differential rotation.

- Sunspot cycles every ~11 years reflect the reversal of magnetic polarity.

- Active regions store energy that can release as solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

Impact on Planetary Environments and Space Weather

The Sun’s outpouring of particles and electromagnetic radiation shapes the atmospheres, surfaces, and magnetic environments of all Solar System bodies. From auroras dancing on planetary poles to the erosion of Martian air, solar activity drives a wealth of phenomena collectively known as space weather.

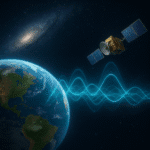

Solar Wind and the Heliosphere

A continual stream of charged particles—primarily electrons and protons—flows outward as the solar wind. This supersonic plasma forms a protective bubble called the heliosphere, within which planets orbit safely cushioned from interstellar radiation. The heliosphere’s boundary, the heliopause, marks the edge of the Sun’s dominion.

Planetary Magnetospheres and Atmospheres

- Earth: Our strong magnetic field deflects much of the solar wind, producing spectacular auroras near the poles when particles funnel along field lines into the upper atmosphere.

- Mars: Weak remnant magnetism allowed the solar wind to strip much of its atmosphere, contributing to its current cold, dry state.

- Jupiter: The largest magnetosphere collects volcanic material from the moon Io, creating intense radiation belts and “auroral footprints” in Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Solar Flares and Coronal Mass Ejections

Sudden releases of magnetic energy produce solar flares—bursts of X-rays and ultraviolet radiation—and CMEs that hurl billions of tons of plasma into space. When directed toward Earth, these events can disrupt satellites, power grids, and communications networks.

Long-Term Climate Influences

Variations in solar output, such as the Maunder Minimum in the 17th century, correlate with cooler climatic periods like the “Little Ice Age.” While the Sun’s luminosity remains relatively stable, small fluctuations can modulate Earth’s climate over decades to centuries.

Through its complex blend of gravitational, magnetic, and radiative forces, the Sun continuously shapes the architecture and evolution of our Solar System. Its influence spans from the earliest stages of planetary formation to the present-day dynamics of space weather, reminding us that our star is far more than just a distant glowing sphere—it is the very engine that drives cosmic change.