A thrilling journey into the methods astronomers employ to unveil the hidden atmospheres of distant exoplanets reveals the ingenious marriage of cutting-edge technology and fundamental physics. By analyzing the faintest signals filtered through alien skies, scientists can identify the chemical fingerprints that hint at planetary climates, weather phenomena, and even the potential for life. This article explores the key techniques—transit spectroscopy, direct imaging, and thermal emission studies—and highlights recent advances that push the boundaries of what we can learn about worlds light-years away.

Transit Spectroscopy: Peering through Alien Skies

Transmission Spectroscopy Basics

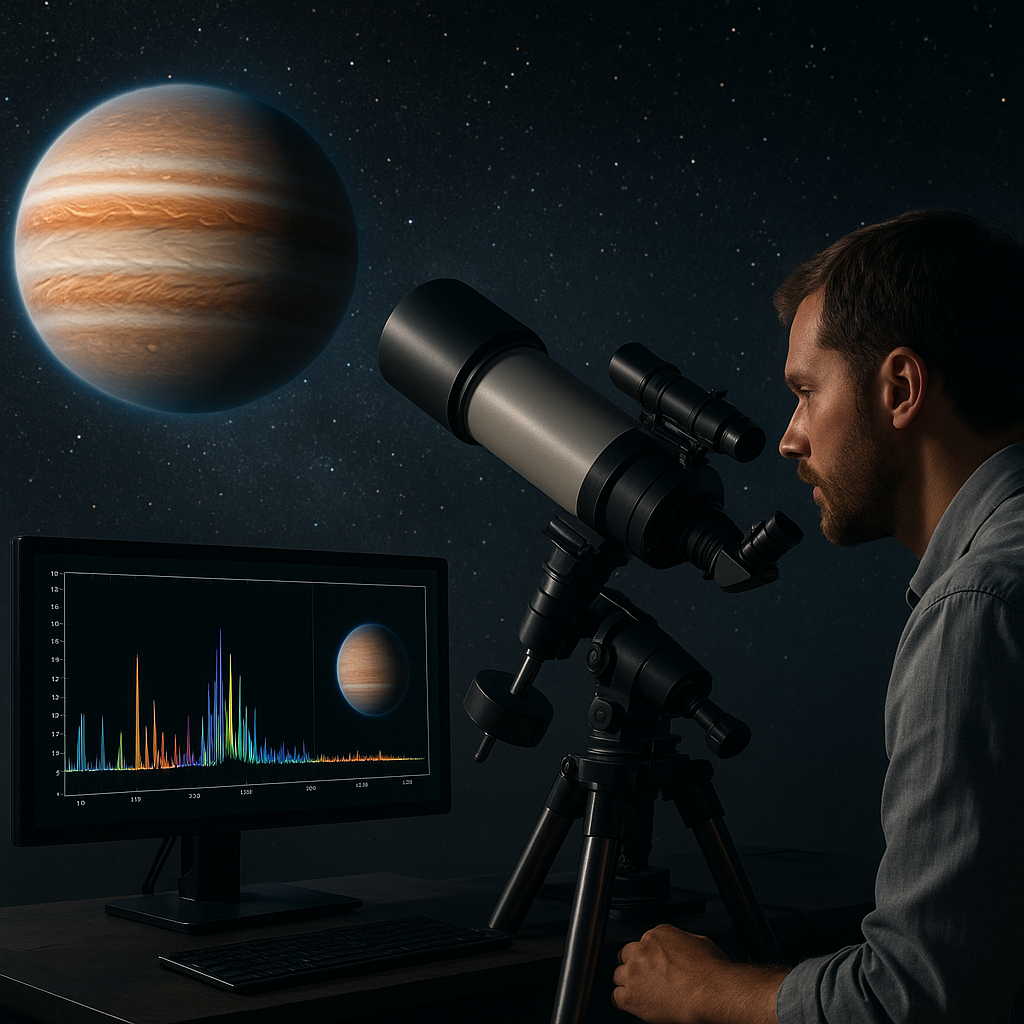

When a planet passes in front of its star as seen from Earth—a phenomenon known as a transit—a tiny fraction of starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere before reaching our telescopes. Molecules and atoms absorb specific wavelengths, leaving characteristic dark lines in the observed spectrum. By comparing the star’s spectrum during transit to its baseline spectrum out of transit, astronomers can deduce which compounds reside high above the planet’s cloud tops.

Key Absorption Features

Different molecules absorb at distinct spectral bands. For example:

- Water vapor shows strong absorption around 1.4 micrometers in the near-infrared.

- Sodium reveals itself in narrow lines near 589 nanometers, in the visible band.

- Methane and carbon dioxide leave wider features at 1.6–2.0 micrometers.

- Potassium can appear at 770 nanometers under high-altitude conditions.

Detecting these signals requires extremely precise instruments, as the change in transit depth caused by atmospheric absorption can be less than 0.1% of the total starlight.

Challenges and Mitigation

Ground-based observatories must cope with Earth’s own atmospheric absorption and turbulence. Techniques such as differential photometry, which compares the target star to nearby reference stars, help correct for variations in Earth’s seeing conditions. Space telescopes, free from atmospheric interference, excel at ultra-precise measurements in the infrared and visible domains. Innovative data pipelines and machine-learning algorithms further refine the extraction of faint exoplanet signals from noisy backgrounds.

Direct Imaging and Thermal Emission

Overcoming the Star’s Glare

Directly imaging an exoplanet requires blocking the host star’s blinding light by factors of a million or more. Coronagraphs and starshades are ingenious devices designed to suppress starlight. A coronagraph inside a telescope uses masks and carefully shaped mirrors to create destructive interference for starlight, while allowing planet light to pass through. A starshade, flying tens of thousands of kilometers in formation with a space telescope, casts a precise shadow that shields the telescope from its star’s glare.

Spectroscopy of Emitted and Reflected Light

Once the planet’s light is isolated, astronomers can perform spectroscopy on two types of signals:

- Reflected light in the visible and near-infrared, carrying information about cloud coverage, surface composition, and molecular signatures.

- Thermal emission in the mid-infrared, revealing the planet’s temperature profile and potential heat redistribution by atmospheric winds.

By measuring the spectrum of thermal emission, scientists can infer the planet’s dayside temperature, determine whether a thick atmosphere evens out temperature contrasts, and identify strong emitters like carbon monoxide.

Case Studies: Young Gas Giants

Direct imaging has excelled in capturing self-luminous, young gas giants orbiting far from their stars. These planets, still cooling after formation, shine brightly in the infrared. Telescopes like the Very Large Telescope (VLT) with its SPHERE instrument, and the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), have revealed methane and water in the spectra of these juvenile worlds. Such detections rely on adaptive optics systems that correct for atmospheric distortion in real time, delivering razor-sharp images.

Advancements in Instrumentation and Techniques

Next-Generation Space Observatories

The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) marked a leap forward for exoplanet atmosphere research. With its 6.5-meter mirror and coverage from 0.6 to 28 micrometers, JWST can observe both transit spectra and direct emission signatures with unprecedented sensitivity. Future missions like the Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (ARIEL) are dedicated to surveying hundreds of exoplanets to build a statistical understanding of atmospheric diversity.

High-Dispersion Spectroscopy

High-dispersion spectrographs spread light into extremely fine wavelength bins, revealing subtle shifts due to the planet’s orbital motion. This technique—often called the cross-correlation method—enhances the detection of molecules by matching observed features to template spectra. It also allows measurement of atmospheric winds through Doppler shifts, offering a glimpse into weather patterns on alien worlds.

Ground-based ELTs and Adaptive Optics

The upcoming Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs), such as the European ELT and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), will open new windows for exoplanet atmosphere studies. Their >30-meter apertures promise dramatically increased light-gathering power and resolution. Equipped with state-of-the-art adaptive optics, these giants will resolve planets at smaller star–planet separations, enabling the study of temperate, potentially habitable worlds in reflected light.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Telluric Contamination

For ground-based work, removing the imprint of Earth’s atmosphere remains a formidable challenge. Telluric lines from water vapor and molecular oxygen must be modeled and subtracted with high precision. Observatories at extremely dry, high-altitude sites—such as the Atacama Desert—help reduce these effects, while advanced algorithms strive to separate planetary signals from terrestrial noise.

Clouds and Hazes

Clouds and photochemical hazes can mute or mask key molecular features in an exoplanet’s spectrum. Understanding aerosol formation and microphysics in exotic environments is crucial. Laboratory experiments simulating high-temperature atmospheres, along with 3D climate models, aim to predict cloud species such as silicates or sulfides, improving the interpretation of flat or muted spectra.

The Search for Biosignatures

The ultimate dream is to detect biosignature gases—molecules like oxygen, ozone, methane, or even more exotic compounds—that could indicate biological activity. Achieving this requires pushing systematic errors below parts per million in transit measurements and obtaining high-resolution direct spectra of Earth-sized planets around nearby stars. Collaborative efforts between astronomers, chemists, and biologists will refine the list of target species and the statistical frameworks for assessing habitability.

Interdisciplinary Synergy

Progress in exoplanet atmosphere detection thrives on synergy between observational astrophysics, laboratory spectroscopy, and theoretical modeling. High-precision laboratory measurements of molecular line lists feed into retrieval algorithms that invert observed spectra to yield temperature, pressure, and composition profiles. The continuous feedback loop between data and models accelerates the refinement of techniques and deepens our understanding of diverse planetary atmospheres.

Conclusion

As we refine our tools and methods, the ability to characterize exoplanet atmospheres moves from detection of simple gases toward detailed weather maps and composition curves. Each new spectrum enriches our understanding of planetary physics and chemistry beyond the solar system. The coming decades promise an era where the diversity of alien skies will be brought into focus, transforming distant points of light into worlds with discernible climates, landscapes, and perhaps even life.