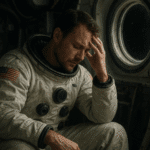

Exploring the human mind beyond Earth’s atmosphere reveals a realm of challenges that extend far beyond the technical hurdles of rocket science. Long-duration space missions demand a level of resilience and psychological preparedness unparalleled in terrestrial exploration. As astronauts venture deeper into the universe, understanding how they cope with isolation, confinement, and prolonged separation from home becomes a mission-critical endeavor.

Isolation and Confinement Effects

Spacecraft interiors and habitats on lunar or Martian surfaces offer limited privacy and a constant proximity to crewmates. This environment can trigger a cascade of psychological responses:

- Boredom and Monotony: Repetitive tasks and unchanging surroundings may lead to reduced motivation and mental fatigue.

- Sleep Disruption: Absence of natural light cycles in deep space can alter circadian rhythms, impacting cognitive performance.

- Heightened Anxiety: The vastness of space and perceived lack of control over external hazards can amplify stress levels.

Research conducted in analog facilities on Earth, such as polar stations and underwater habitats, demonstrates that isolation can erode mood stability and accelerate irritability. Adaptive design strategies, including flexible lighting systems and modular living spaces, aim to mitigate these effects by creating an environment that feels more dynamic and personalized.

Psychological Stressors and Coping Mechanisms

The constellation of stressors faced by crew members encompasses both internal and external pressures:

- Operational Demands: Maintenance of life support systems and scientific experiments requires constant vigilance.

- Risk Perception: Awareness of mission-critical failures, such as radiation exposure or system malfunctions.

- Emotional Strain: Separation from family, uncertainties about mission outcomes, and potential conflict among crewmates.

To cope, astronauts employ a variety of strategies. Cognitive reframing helps in shifting focus from stress-inducing aspects to meaningful objectives. Structured schedules, incorporating leisure activities like reading or music, foster a sense of normalcy. Additionally, virtual reality simulation systems enable immersive experiences that can transport crew members back to Earth’s natural settings, alleviating homesickness and anxiety.

Interpersonal Dynamics and Group Cohesion

Successful missions hinge on effective teamwork and communication. When a small crew lives in close quarters for months or years, social dynamics play a pivotal role:

- Role Clarity: Clearly defined responsibilities reduce overlap and conflict.

- Conflict Resolution: Training in mediation techniques empowers crew members to address disagreements constructively.

- Emotional Support: Peer-to-peer encouragement strengthens bonds and fosters a supportive environment.

Studies emphasize the importance of fostering interpersonal trust early in mission preparation. Teams engage in trust-building exercises, such as group problem-solving challenges and resilience workshops. The presence of a trained counselor or psychologist, either on-site or via real-time communications, can provide an outlet for stress and mediate tensions before they escalate.

Technological Tools and Support Systems

Advancements in technology are pivotal to supporting mental health on extended missions. Innovative solutions include:

- Telemedicine Platforms: Enabling psychological consultations through audio, video, and biometric data monitoring.

- Artificial Intelligence Assistants: Providing reminders, mood tracking, and interactive companionship that can adapt to individual needs.

- Biofeedback Devices: Monitoring vital signs and stress indicators to prompt relaxation exercises or adjustments in workload.

Integrating these tools into daily routines helps astronauts maintain autonomy over their well-being. For instance, AI-driven mood analysis can detect early signs of depression and recommend personalized interventions. Regular data uploads to ground teams allow for proactive support, ensuring that psychological needs are addressed swiftly.

Training, Selection, and Adaptation

Pioneering missions to Mars or beyond require selecting individuals with unique psychological profiles. Candidate assessments focus on traits such as adaptability, emotional stability, and problem-solving under pressure. Training regimens simulate extreme conditions, including:

- Analog Missions at remote research stations to test endurance and social compatibility.

- Virtual Reality Scenarios replicating emergencies like cabin depressurization or equipment failure.

- Stress Inoculation Exercises designed to build tolerance against high-pressure decision-making.

Through iterative exposure and guided reflection, astronauts develop robust coping mechanisms that can be deployed when real emergencies arise. This preparatory phase also helps identify potential interpersonal conflicts, allowing for team reconfiguration before launch.

Future Directions in Space Psychology

As missions grow longer and distances increase, research priorities evolve to address new challenges:

- Prolonged Autonomy: With delayed communication, crews must make critical decisions without real-time ground support.

- Cross-Cultural Teams: International collaboration introduces diverse perspectives but also cultural nuances that require tailored communication strategies.

- Moon and Mars Habitats: Environmental psychology will guide habitat design to optimize well-being in partial gravity environments.

Emerging studies explore the potential of psychopharmacology and neuromodulation techniques to enhance mood stability and cognitive performance. Ethical considerations are paramount, ensuring that any interventions respect crew autonomy and long-term health. As humanity prepares to extend its presence beyond low Earth orbit, the integration of psychological science and technology remains a cornerstone of mission success.