The Sun occasionally releases powerful bursts of energy known as solar flares, which can interact with Earth’s magnetic environment and pose challenges for our modern technological infrastructure. These eruptions propel streams of charged particles and intense electromagnetic radiation across space, influencing everything from high-altitude aviation to everyday electronics. Understanding the mechanisms behind these solar explosions and their terrestrial effects is crucial for preparing critical systems against potential disruptions.

Origins and Characteristics of Solar Flares

Solar flares originate in regions of concentrated magnetic fields on the Sun’s surface, particularly near sunspots. When twisted magnetic field lines reconnect suddenly, an enormous amount of energy is released in the form of light, heat, and charged particles. This process is often accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which propel dense clouds of plasma into interplanetary space.

- Energy release: Flares can unleash up to 1025 joules of energy within minutes.

- Radiation spectrum: Emissions span radio waves, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays.

- Particle acceleration: Protons and electrons accelerated to near-relativistic speeds.

Classification of flares relies on peak X-ray brightness measured by space-based instruments. The categories—A, B, C, M, and X—indicate increasing intensity, with X-class flares representing the most severe events. Even a moderate M-class flare can induce significant changes in the upper atmosphere, while X-class flares have the potential to trigger widespread geomagnetic storms.

Magnetic Reconnection and Particle Release

At the heart of each flare lies magnetic reconnection, a dynamic process where oppositely directed magnetic field lines break and rejoin. This releases magnetic energy and accelerates particles outward. Observations from missions such as NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) reveal rapid changes in coronal loops and bright flare kernels, signifying localized heating of millions of kelvins.

Interactions with Earth’s Magnetosphere and Ionosphere

When charged particles from solar flares reach Earth, they interact with our planet’s magnetic shield—the magnetosphere. This interaction can compress or distort magnetic field lines, leading to enhanced currents in the upper atmosphere and induction of electrical currents in the ground.

The ionosphere, a layer of charged particles extending from about 50 to 600 kilometers above Earth, is especially vulnerable to sudden influxes of high-energy photons and electrons. Increased ionization in this region alters radio wave propagation, causing degradation or complete blackout of high-frequency (HF) communications used by aircraft and marine vessels.

- Sporadic E-layers: Sudden layers of dense ionization disrupt navigation signals (GPS).

- Polar cap absorption: At high latitudes, enhanced X-rays can completely absorb HF signals.

- Shortwave fadeouts: Daytime X-ray enhancements lead to signal loss for tens of minutes.

Auroral Displays and Currents

One of the most visually spectacular effects of solar flare–induced disturbances is the intensification of auroras. As energetic particles spiral along magnetic field lines into polar regions, collisions with atmospheric gases excite atoms and molecules, producing luminous curtains of green, red, and purple light. Simultaneously, enhanced ionospheric currents can induce geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) in long conductors such as pipelines and power lines, posing risks to infrastructure integrity.

Effects on Modern Technology

The pervasive reach of modern electronics makes us increasingly susceptible to solar-driven disruptions. From satellites orbiting Earth to ground-based networks powering cities, several technological systems are at risk during intense solar activity.

Satellite Operations and Risk of Failure

Satellites operating in low Earth orbit and geostationary orbit encounter elevated levels of high-energy radiation that can damage sensitive electronics, degrade solar panels, and cause data corruption in memory modules. During severe events, operators may place satellites into safe mode to prevent hardware damage, leading to temporary loss of services such as weather monitoring, television broadcasting, and global communication networks.

Power Grids and Ground Infrastructure

Large-scale power grids spanning continents are vulnerable to rapid changes in Earth’s magnetic field. When geomagnetic disturbances induce fluctuating currents in transmission lines, transformer cores can saturate, leading to voltage instabilities and potential equipment overheating. Historical incidents—such as the 1989 Hydro-Québec blackout—demonstrate how a severe geomagnetic storm can plunge millions into darkness within seconds.

- Transformer damage: Excessive GICs can cause irreparable harm to expensive grid components.

- Voltage collapse: Reactive power consumption spikes may trigger grid-wide failures.

- Protective measures: Automated relays can disconnect vulnerable segments to prevent damage.

Communication and Navigation Disruptions

High-frequency and satellite-based communication systems both feel the impact of solar disturbances. HF radio operators may experience complete blackouts during daytime flares, while satellite navigation signals (GPS, GLONASS, Galileo) can suffer from range errors due to ionospheric scintillation. These inaccuracies affect aviation safety, maritime operations, and any application relying on precise timing.

Monitoring, Forecasting, and Mitigation Strategies

Advances in space science and observational technology have made it possible to monitor solar activity in real time and issue early warnings. Coordinated efforts by agencies like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and ESA’s Space Weather Service Network aim to forecast events and provide actionable data to stakeholders.

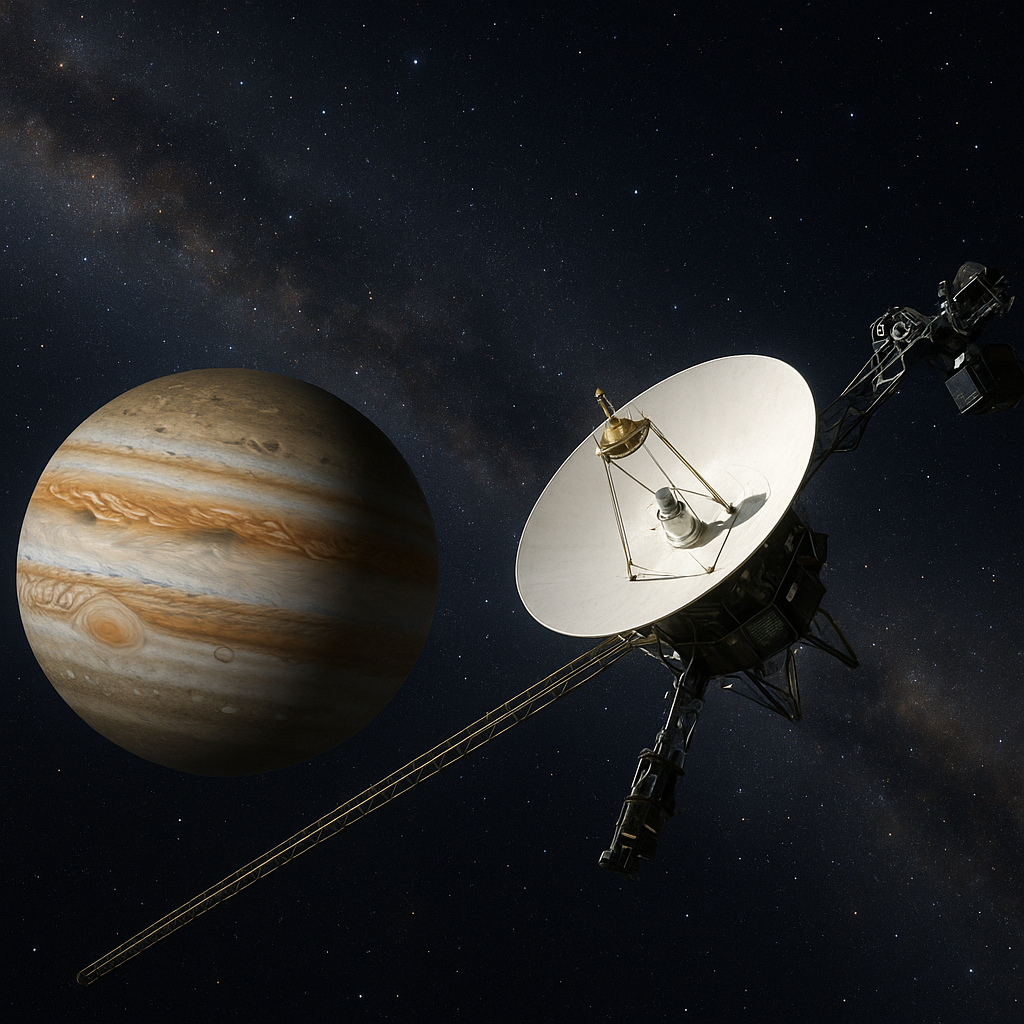

Space-Based Observatories

Satellites such as SDO, SOHO, and the Parker Solar Probe continuously observe the Sun in multiple wavelengths. These instruments track active regions, measure magnetic field strengths, and detect emerging coronal mass ejections well before they impact Earth. Early detection enables operators to implement protective protocols, such as adjusting satellite orientations and powering down vulnerable components.

Ground-Level Precautions

On the terrestrial front, power companies deploy GIC monitoring systems and employ grid hardening techniques—installing series capacitors, improving transformer design, and refining operational procedures. Aviation authorities adjust flight paths to avoid polar routes during severe events, reducing exposure to harmful radiation for crews and passengers.

- Enhanced forecasting: Model-driven predictions of particle arrival times and intensity.

- Operational protocols: Standardized response plans for communication and power sectors.

- International collaboration: Shared data and coordinated alerts across space weather communities.

The interplay between the Sun’s explosive behavior and Earth’s technological systems underscores the importance of continued research and robust infrastructure management. By combining observation, modeling, and practical safeguards, society can better withstand the next powerful solar burst and preserve the vital networks that power our modern way of life.