The cultivation of fresh produce beyond Earth’s atmosphere represents one of the most intriguing challenges of modern space exploration. As missions extend in duration and venture farther from our home planet, the ability to produce food in situ becomes increasingly vital. This article examines the methods, challenges, and future prospects for growing crops in the harsh environment of outer space, shedding light on the ingenuity required to support life on long-duration missions.

Historical Perspectives on Space Agriculture

Early experiments in the 1960s and 1970s laid the groundwork for contemporary research. Scientists recognized that reliance on earthbound resupply missions would not be feasible for extended expeditions. The Soviet Union’s NASA counterpart carried out rudimentary tests with sprouting seeds onboard Salyut stations, demonstrating that even in microgravity, plant life can germinate. These pioneering studies highlighted the extraordinary adaptability of botanical systems when provided with proper environmental controls.

Key Systems for Cultivating Plants in Orbit

Hydroponics

Hydroponics involves growing plants in a nutrient-rich water solution, completely eliminating the need for soil. In an orbiting module, traditional soil poses risks of contamination and uncontrolled microbial growth, so hydroponics offers a closed-loop solution. Roots are suspended in water pumped through channels, delivering precisely measured mineral salts and oxygen. Early tests on the International Space Station (ISS) used small-scale hydroponic trays to grow leafy greens. These setups require pumps, reservoirs, sensors, and LED lighting to maintain optimal conditions.

Aeroponics

Aeroponics takes the concept further by delivering nutrients as a fine mist. This method increases oxygen availability to roots and reduces water consumption by up to 95% compared to soil-based agriculture. Aeroponic chambers on Earth have demonstrated rapid growth cycles and high yields. In microgravity, controlling droplet behavior is complex: pumps and ultrasonic nozzles must be finely tuned to avoid clustering. Nevertheless, early prototypes onboard stations have successfully supported lettuce and herb production.

Bioregenerative Life Support

Beyond simply growing food, bioregenerative systems aim to recreate ecological cycles. Plants absorb carbon dioxide exhaled by crew members and release oxygen through photosynthesis. Wastewater and organic refuse can be filtered and repurposed as fertilizer, mimicking terrestrial nutrient loops. Designing a fully closed ecological system remains a formidable task, requiring integration of microbial reactors, plant growth chambers, and advanced filtration technologies to ensure sustainable resource turnover.

Environmental Challenges in Orbital Farms

Operating an agricultural module in space involves contending with several harsh factors simultaneously.

- Microgravity: Without gravity, root systems must adapt to fluid behavior that no longer drains downward. Researchers employ capillary wicks, porous substrates, or foam matrices to anchor roots and distribute water.

- Radiation: Outside Earth’s protective magnetosphere, plants are exposed to cosmic rays and solar particle events. Shielding can mitigate damage, but genetic and biochemical responses of plants to radiation remain an active field of study.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Spacecraft modules can experience wide thermal variations. Precise thermal control via insulation, heat exchangers, and active cooling is essential to maintain optimal growth temperatures.

- Pollination and Crop Yield: Insects cannot be relied upon, and human-assisted pollination is labor-intensive. Genetic engineering of self-pollinating cultivars or mechanical pollination tools offers potential solutions.

- Microbial Balance: Beneficial microbes must be preserved to support nutrient cycling, while harmful pathogens must be kept in check. Sterilization protocols and microbiome monitoring systems are integral to system design.

Case Studies: Successful Space-Grown Crops

Several plant species have proven well-suited for microgravity agriculture:

- Leafy Greens: Lettuce, kale, and spinach have fast germination cycles and low mass, making them ideal for hydroponic trials on the ISS.

- Herbs: Basil and dill thrive under LED spectra tailored to their photosynthetic peaks, adding flavor diversity to astronaut diets.

- Tomatoes: Dwarf varieties with indeterminate growth patterns have yielded ripe fruit in controlled modules, showcasing the potential for protein-rich crops.

- Grain Precursors: Early research into wheat and barley aims to provide carbohydrate sources, though their longer growth cycles present scheduling challenges for mission planners.

Toward Lunar and Martian Agriculture

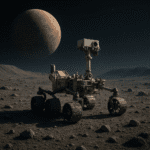

Growing food on the Moon or on Mars introduces new variables. Regolith—the native soil analog—lacks organic matter and may contain toxic perchlorates. Scientists have proposed mixing regolith with hydroponic media or using bioremediation bacteria to detoxify it. Greenhouses on the lunar surface must withstand micrometeorite impacts and severe temperature swings exceeding 200°C between lunar day and night.

On Mars, reduced gravity (about 38% of Earth’s) could partially alleviate fluid distribution issues, but dust storms and lower sunlight intensity require powerful LED lighting and robust filtration systems. Closed habitats might incorporate transparent domes or subsurface structures shielded by regolith for radiation protection.

Innovations and Future Directions

Research continues on enhancing crop resilience and optimizing resource use. Key areas of focus include:

- Genetic Engineering: Editing plant genomes to improve nutrient content, stress tolerance, and growth rate under space conditions.

- Automated Farming: Robotic arms perform seeding, harvesting, pruning, and pollination, minimizing crew workload.

- Artificial Intelligence: AI algorithms monitor sensor data to adjust lighting, nutrient delivery, and environmental controls in real time.

- Synthetic Biology: Designing novel organisms or microbial consortia that can fix nitrogen, degrade waste, or secrete valuable compounds alongside crops.

As human presence in space expands, the mastery of off-world agriculture will become a cornerstone of mission success. The ongoing collaboration between aerospace engineers, biologists, and agronomists will shape the next era of exploration, where every bite of fresh produce contributes to the well-being of crew members and the sustainability of extraterrestrial outposts.